We celebrate the tenth anniversary of the General Law on the Rights of Children and Adolescents (LGDNNA) in Mexico, which meant an important advance for the protection of children and adolescents in general, and migrant children in particular.

10 years ago, there was global talk in the media about migrant children and adolescents who arrived seeking protection at the southern border of the United States, after crossing on foot throughout Mexico. According to statistics from U.S. authorities for its fiscal year 2014, in that year they found 68,541 unaccompanied children, and for the first time there were more Central American children than Mexicans.1 Due to the context of human mobility in Mexico and the region, and the high participation of children and adolescents, it was considered necessary to include a chapter in the LGDNNA that specified the special measures and responsibilities for migrant children and adolescents in the country.

It is interesting to compare the information on migrant children and adolescents in 2014 with that of 2024. To measure how many migrant children and adolescents there were in each year and where they are from, we only have information from the immigration authorities, that is, administrative records of the National Institute of Migration (INM) converted into statistics by the Migration Policy Unit (UPM) of the Ministry of the Interior.

In 2014, the UPM published data on “minors presented to the immigration authority,” which means migrant children detained by INM. In that year, there were 23,096 children and adolescents out of 127,149 migrants (children and adolescents were 18% of the total). Of this group, 10,943 children and adolescents were “unaccompanied” (47%), and of these, 98% came from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. Although some other Mexican institutions attended to children and adolescents on the move, such as the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) and some shelters of the National System for the Integral Development of the Family (SN-DIF), to date there is no data that can give a more complete picture. For this reason, UPM/INM data still give us the best idea of the dimension and profile of migrant children in Mexico in recent years.

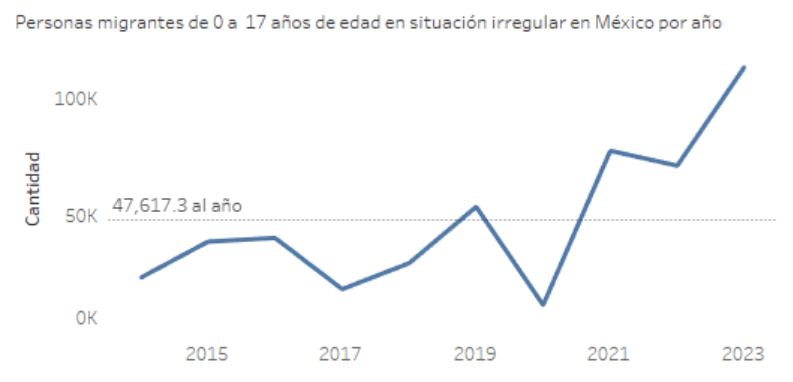

Today, precisely thanks to the LGDNNA, we no longer see data on children and adolescents “presented” (detained), and official statistics speak of “children and adolescents in a situation of irregular migration”. Migrant children and adolescents today must be represented by the Attorney General’s Office for Protection and channeled into the DIF System, instead of being detained by the INM in Migrant Detention Centers. The same UPM continues to publish data based on INM records, and we see that this year, between January and August, 180,444 children and adolescents were registered. The increase in the number of migrant children and adolescents in 10 years can have several explanations. For example, the political and socioeconomic situation in Venezuela and other countries such as Colombia, Ecuador, Chile, Peru and Haiti caused many families, including children, to travel to Mexico, something that did not happen in 2014.

It is worth noting that the number and percentage of unaccompanied children identified by the Mexican authorities has decreased compared to the figures for 2014. In 2024, 4,383 unaccompanied children identified by Mexican authorities represented only 4% of the total number of children identified (108,444). Although the way in which the Mexican government registers this population has changed, the contrast with 2014 is clear: in that year, 10,943 of 23,096 children and adolescents were unaccompanied: 47%. Of the unaccompanied children identified in 2024, a large part are nationals of Guatemala and Honduras: 71% of the total number of unaccompanied children. How can it be explained that the number of unaccompanied children and adolescents is lower? It is difficult to be certain with the available data. In addition, “separated children,” traveling with adults who are not their parents, cannot even be identified in statistics.

This brief exercise of comparing data between 2014 and 2024 on migrant children and adolescents in Mexico leaves us with some reflections. In the first place, Article 99 of the LGDNNA establishes that: “The National DIF System must design and manage databases of unaccompanied foreign migrant children and adolescents, including, among other aspects, the causes of their migration, transit conditions, their family ties, risk factors at origin and transit, information on their legal representatives, data on their accommodation and legal situation, among others”.

It is important to note that the information that Mexico currently publishes on migrant children and adolescents does not have the perspective of human rights protection, but that of migration records. This is problematic, because it does not allow us to understand how many children and adolescents are effectively represented by the Protection Attorney’s Offices and are cared for by Social Assistance Centers (CAS) or authorized spaces. Similarly, it does not allow us to know if they have assessments carried out by multidisciplinary teams of the Attorney’s Offices, as well as protection measures and plans for the restitution of rights. Finally, we do not know how many migrant children and adolescents remain and integrate into Mexican communities, how many are reunified with family members in a third country or returned to their country of origin.

Due to this lack of information, in Mexico’s last review in August 2024, the Committee on the Rights of the Child reiterated in its observations that there is an urgent need to improve the information and data system in Mexico, in particular for the collection of disaggregated data on asylum-seeking and refugee children, including unaccompanied and separated children.2

REDIM and KIND agree that information on children and adolescents on the move in Mexico, if it is a priority within public policy for children, cannot continue to depend on migratory records and must have the perspective of protection of rights that the LGDNNA has. Finally, without an information system led by child protection agencies, we do not know how the best interests of migrant children and adolescents are being determined, taking into account their voice and participation. We call on the newly elected government to reiterate its commitment to migrant children, strengthening the path of rights that had already been marked out with the LGDNNA.